A Stunning Trio of Early Christian (3rd century) Inscriptions from Biblical Armageddon: ‘God Jesus Christ,’ Five Prominent Named Women, a Named Centurion, a Eucharist Table, and Two Fish

- Professor Christopher Rollston (rollston@gwu.edu)

George Washington University, Department of Classical and Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations

- An Overview.

On occasion, inscriptions with some very important content will come to light (much like the Mesha Stele, the Tel Dan Inscription, or the Kuntillet Ajrud inscriptions, etc.). With these three Megiddo Mosaic inscriptions, written in Greek, hailing from an early period of Christianity (early 3rd century), and the region of the ancient city of Megiddo (referenced once in the New Testament as “Armageddon,” or better “Har-Mageddon, in Revelation 16:16), we have just such a case. Note that the site of these inscriptions is not Tel Megiddo, but close to it. The name of the site in the preliminary publication is given as Kefar ‘Othnay (Tepper, Di Segni, Stiebel 2005).

In terms of the room in which these inscriptions are found, the preliminary publication refers to it as a 3rd century “Christian Prayer Hall.” I have a slight preference for the broader term 3rd century “Christian Worship Hall,” since this seems to be a place for the celebration of Eucharist, which would have included Eucharist, prayers, and hymns (based on New Testament and Early Christian discussions of Christian worship services). In other words, “prayer hall,” seems a bit too restrictive of a term, from my perspective, as that term might be understood to imply that prayers were the primary thing that occurred in this hall. Of course, someone could also justifiably refer to this as a “church,” I suppose, in light of the fact that the term ekklēsia (normally translated “church”) signifies in the New Testament not a building but rather a church meeting (e.g., 1 Corinthians 11:18), or the Christian community living in one place (e.g., Acts 5:11; 1 Corinthians 4:17; Philippians 4:15, etc.), or house churches (e.g., Romans 16:5; 1 Corinthians 16:19). But the problem with the term “church,” is that this term (post the New Testament) gradually came to signify large(r) buildings, and this is not what we have at Megiddo either. Thus, I have settled on “worship hall” as a useful designation.

In terms of the content of the inscriptions themselves, (1) we have one which includes this sequence of words: “God Jesus Christ,” as well as reference to a “table” which is most readily understood as a Eucharistic table, and a Greek word for “memorial.” Strikingly, this inscription was commissioned by a prominent woman named Akeptous. Following the lead of the authors of the preliminary publication, I refer to this mosaic inscription as “the Akeptous Inscription.” (2) In addition, we have one inscription with an imperative verb, exhorting its readers to remember four women, whose names are also contained in this inscription: Primilla, Kuriake (Cyriaca), Dorothea, and Chreste. The fact that these women are the sole content of this inscription certainly reveals something about the high status of these women in this Christian community. Following the preliminary publication, I refer to this as “the Women’s Inscription.” (3) Finally, one of these inscriptions mentions a centurion with the Roman named Gaianus (his Greek name was Porphyrius) as the prominent benefactor who made the donation for the mosaic, replete with a medallion of two fish. The name of the artisan who set (or made and placed) the mosaic is also given, Brutius, a good Roman name. Following the preliminary publication, I refer to this inscription as the “Gaianus Inscription.” Within this post, I will deal with all three inscriptions, but I will devote more of my attention at this time to the Akeptous Inscription, in order to discuss in some depth usage of the term “God Jesus Christ.”

In terms of the date for this Early Christian Worship Hall, the preliminary edition contends that it was during the early 3rd century CE (ca. 230 CE). Of course, some people have often assumed that prior to the Edict of Toleration in 312 CE, Christianity was a persecuted religion and so some sort of worship hall, especially one associated with an officer in the Roman army, would not have been possible. It should be remembered, however, as nicely articulated in the preliminary publication (passim), that there was an ebb and flow to persecutions of Christians prior to ca. 312 CE.

One of the things that I do in this post is to read these inscriptions through the lens of the New Testament, since these inscriptions do hail from a time period not long after the closing of the New Testament, as it were. Moreover, there will also be some references to Early Christian sources, as well as to some of the most relevant Roman sources (from Pliny the Younger to Celsus, the Emperor Julian, etc.).

- Introduction to the Archaeological Site

According to the very fine preliminary excavation report of Yotam Tepper, Leah Di Segni, and Guy Stiebel (2005, p. 5), excavations were conducted between 2003 and 2005 of ca. 3000 square meters (3 dunams) “inside the ancient Jewish settlement of Kefar ‘Othnay” (also now known as the “Megiddo Prison,” because of usage in the modern period), near “the headquarters of the Roman Sixth Legion Ferrata” (i.e., the “Sixth Ironclad Legion,” with the Arabic place-name “el-Lajjun” preserving the Latin term “Legio), “and the city of Maximianopolis,” all of which are mentioned in Roman and Byzantine sources (Tepper, Di Segni, Stiebel 2005, 5; see also especially “Legio” by Adams, David, Tepper 2014). Furthermore, this site is also very near the site of Tel Megiddo, a site mentioned in the New Testament book of Revelation as “Har-Magidon (Rev 16:16, literally meaning “the mountain of Megiddo,” with the Hebrew and Aramaic word for “mountain” being “har,” written in Greek as “ar” since Greek does not have a letter “h”), a word often transliterated into English translations as “Armageddon.” This excavation was a salvage excavation, and it was conducted on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA). Archaeological remains dating from the Early Roman period to the late Byzantine periods were found. The excavations were fairly extensive and reveal aspects of “daily life in the rural settlement that developed and expanded alongside the Roman army camp” (Tepper, Di Segni, Stiebel 2005, 5).

Significantly, during the course of the excavations “a large residential building, dating to the third century CE, was exposed during the excavation of the settlement” (Tepper, Di Segni, Stiebel 2005, 5). Moreover, the conclusion of the publication team, based on archaeological finds, is that this large residential building (part of excavation “Area Q”) “was used by soldiers of the Roman army and that one of its wings functioned as a prayer hall for a local Christian community” (Tepper, Di Segni, Stiebel 2005, 5). This so-called “prayer hall,” was rectangular, measured “about 5 x 10 m,”, and it was paved, “with a mosaic floor adorned with geometric patterns and three Greek inscriptions” (Tepper, Di Segni, Stiebel 2005, 24). Because the tesserae of the mosaic are of uniform size and shape, the authors of the preliminary suggest that “the mosaic was the work of a single artist” (Tepper, Di Segni, Stiebel 2005, 25). It is also noted in this publication that “the layer that covered the mosaic contained pottery sherds, mostly of jars.” And it is further noted that “on top of this layer were several fragments of fresco and numerous pieces of thick gray multi-layered plaster” (Tepper, Di Segni, Stiebel 2005, 25-26). Based on the typology of the excavated pottery, the preponderance of the numismatic evidence (i.e., the coins which were excavated), and the typology of the script of the Greek inscriptions, the preliminary publication contends that this hall was constructed ca. 230 CE (Tepper, Di Segni, Stiebel 2005, 26-34, et passim; note also that there are some military bread stamps with Latin inscriptions, as well as some weapons, discussed especially on pages 29-31). Evidence for these conclusions regarding space-usage and dating are quite cogently argued within the preliminary publication (I may return to the subject of dating based on numismatic evidence in a subsequent blog post, but suffice it to say that I consider the totality of the archaeological and historical evidence, including the numismatic evidence, to support the dating of this hall and the material artifacts found in it to the first half of the third century CE).

Furthermore, along the lines of the presence of prominent Early Christians in this region, it is useful to note that a certain Bishop Paulus of Maximianopolis is mentioned as being present at the Council of Nicaea in 325 CE (A.D. 325), and a certain Megas is reported to have been present in a council in Jerusalem in 518 CE, and a certain Domnus is reported to have been present at a council in Jerusalem in 536 CE (this evidence is all referenced in Tepper, Di Segni, Stiebel 2005, 10, citing Fedalto 1988, 1036). This sort of evidence reveals that it is not surprising that an Early Christian worship hall was present in the region of Kefar ‘Othnay.

- The Three Mosaic Inscriptions in Greek

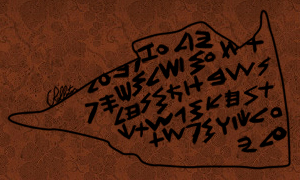

In the center of the hall are two rectangular panels. The southern panel (1.78 m x 2.96 m) contains two mosaic inscriptions in Greek. The preliminary publication refers to these as the Akeptous Inscription and the Women Inscription, with the former six very short lines, and the latter four rather short lines. The northern panel (2.95 x 3.40 m) contains a three-line inscription referred to as the Gaianus Inscription. Within this northern panel is a mosaic “medallion” depicting fish, which the preliminary publication considers to be a tuna and a bass (Tepper, Di Segni, Stiebel 2005, 36). In terms of other aspects of this inscription, ligatures are present on multiple occasions, as are some word dividers. Also, the sigmas are lunate, predictably. At this juncture, I shall provide some comments regarding all three of these inscriptions, often using the lens of the New Testament as a hermeneutical tool for understanding these Early Christian inscriptions. Note that my readings and word-division do not differ with those contained in the preliminary publication, although some of my translations may differ in a modest fashion.

A. The Akeptus Inscription: Readings, Transliteration, and Translation (with word-division added).

1. ΠΡΟΣΗΝΙΚΕΝ (prosēniken)

2. ΑΚΕΠΤΟΥΣ (akeptous)

3. Η ΦΙΛΟΘΕΟΣ (ē philotheos)

4. ΤΗΝ ΤΡΑΠΕ- (tēn trape-)

5. -ΖΑΝ ΘΩ ΙΥ ΧΩ (zan thō iu chō [iu chō = Iēsou Christō] )

6. ΜΝΗΜΟΣΥΝΟΝ (mnēmosunon).

Within the preliminary publication, the following translation is given: “The god-loving Akeptous has offered the table to God Jesus Christ as a memorial” (Tepper, Di Segni, Stiebel 2005, 36). This is a good, very literal, translation. I might wish to translate it, slightly more idiomatically, in the following way: “Akeptous, the friend of God, has offered the table to God Jesus Christ (for) remembrance.”

It is useful to emphasize that in line five, the final three words are all abbreviated. Naturally, the presence of these abbreviations is nicely noted in the preliminary publication (Tepper, Di Segni, Stiebel 2005, 36). The fact that these are definitively to be understood as abbreviations is also signified in the mosaic by a horizontal line above each “word,” which was a common practice in antiquity. For a good discussion of such abbreviations in antiquity, see especially Metzger (1981, 36-37) and Hurtado (2006, 96-98). In any case, as for the Megiddo Mosaic, ΘΩ is an abbreviation for ΘΕΩ (the dative form of the word for God). Along those same lines, ΙΥ is an abbreviation for ΙΗΣΟΥ (the dative form of the personal name “Jesus”; nota bene: both the genitive and the dative of this personal name end in omicron upsilon, that is, ΟΥ, but syntactically it must be the dative form here), and ΧΩ is an abbreviated form of the word ΧΡΙΣΤΩ (that is, the dative form of the title “Christ”).

The phrase “God Jesus Christ” is quite striking, since it seems to be an affirmation of the divinity of Jesus of Nazareth (so also Tepper, Di Segni, Stiebel 2005, 41). Of course, at the Council of Nicaea in 325 CE, this was the official decision (i.e., that Jesus was to be classified as “theos,” alongside the “father”; thus, some of the Nicene creed contains these words about Jesus: “true God out of true God, begotten not made,” with the word “theos” being used). But such a reference in an inscription prior to Nicaea may seem surprising. After all, within even the books of the canonical New Testament, such an emphatic statement as this is hard to find (on this aspect of the New Testament, see the discussion below). Moreover, since the Megiddo inscription uses abbreviations for each of these words (God Jesus Christ), someone might suggest that this phrasing is perhaps just a shortened form of a very common phrase in the introductory greetings of the New Testament letters of the Apostle Paul: “Grace to you and peace from God our father and the Lord Jesus Christ” (Romans 1:7; 1 Corinthians 1:3; 2 Corinthians 1:2; Galatians 1:3; Ephesians 1:2; Philippians 1:2; 1 Thessalonians 1:1; 2 Thessalonians 1:2; Philemon 3; notice that the Pastoral Epistles, often considered Deutero-Pauline or even Pseudo-Pauline, have a slightly different order of the words Jesus and Christ, namely, “God the Father and Christ Jesus our Lord”: 1 Timothy 1:2; 2 Timothy 1:2; Titus 1:4 cf. Colossians 1:21).

On the other hand, the authors of the preliminary publication correctly emphasize that some ante-Nicene Christians do actually use some very similar terminology, revealing that some of the ante-Nicene Christians understood Jesus of Nazareth to be “God.” The authors of the preliminary publication mention the names of some of these ante-Nicene fathers (namely, they list Ignatius of Antioch, Justin Martyr, Irenaeus, Clement of Alexandria, and Hippolytus; see Tepper, Di Segni, Stiebel 2005,41). Since they do not provide precise references, I shall provide a few in order to demonstrate the point more fully. (1) In the writings of Ignatius of Antioch (floruit early 2nd century, writing in Greek), we have the following: “For our God, Jesus Christ, was conceived by Mary…” (Letter to the Ephesians 18:3, using the word theos). Or again, Ignatius uses the following as a means of referring to Jesus: “For our God Jesus Christ, since he is in the Father…” (Letter to the Romans 3:3, again, using the word theos). In Clement of Alexandria (floruit late 2nd century and early 3rd century, writing in Greek), and referring to Jesus as the “Word” (as does the Prologue of the New Testament Gospel of John), wrote the following: “….This Word, who alone is both God and man…” (Exhortation to the Greeks, chapter 1, paragraph 7, using the word theos). In Polycarp (floruit early to mid 2nd century, writing in Greek, but with this section of his Letter to the Philippians, among others, preserved only in Latin translation) we have this statement: “…believe in our Lord and God, Jesus Christ, and in his Father…” (Polycarp, Letter to the Philippians, 12:2, with the Latin translation using the word deus, a good translation of Greek theos). Of course, since someone might suggest that the writings of these ante-Nicene fathers had been modified after the Council of Nicaea (much as Bart Ehrman has contended for some of the textual variants in the New Testament, which were part of Christological dsicussions, Ehrman 1993).

But certain lines of textual evidence converge in such a fashion so as to support taking the Akeptus Inscription from Megiddo at face value, namely, the inscription is most readily understood as affirming the divinity of Jesus of Nazareth. These lines of evidence are (1) the presence of that notion already in the New Testament, (2) and the assumption of non-Christian Roman writers (e.g., Pliny the Younger, Julian, etc.) that (at least some) Christians believed Jesus was theos (in this regard, compare the Ebionite Christians of the 2nd century CE, who did not).

Two New Testament texts in the gospel of John can most readily be understood as referring to Jesus as God. (A) John 1:1 reads as follows: “In the beginning was the Word and the Word was with God, and the Word was God (Greek: theos; note also that reading the totality of John 1:1-18 makes it clear that the author is using the word “Word,” that is, Greek logos, to refer to Jesus). (B) Similarly, John 20:28 has the Apostle Thomas declare this, upon seeing Jesus after the crucifixion: “My Lord and my God” (theos). Within the history of the study of John’s gospel, some in the modern period might want to parse the data differently. However, the fact that this was an ancient understanding of these texts is also corroborated by the position of the Emperor Julian (mid 4th century CE). Thus, distinguished historian Robert Wilken has noted that Emperor Julian contended that “only one of the disciples, John, taught the new idea that Jesus was divine. The other Apostles did not” (Wilken 1984, 179). Furthermore, the late, brilliant New Testament scholar Raymond Brown is representative of a fairly broad consensus in the field in his Anchor Bible Commentary that these Johannine verses are most readily understood as a Johannine affirmation that Jesus of Nazareth was understood as theos, that is, God (Brown 1966, 5, 24, 25; see also Brown 1965, 545-573, especially 563-565; note that Brown also considers Hebrews 1:8-9 to be a New Testament text in which Jesus is regarded by its author as theos, and the hymn in Philippians 2:5-11, with its statement that Jesus was in the morphe theou, “the form of God” could be classified in a similar fashion). In any case, the main point is that although the references are rare, at least in the gospel of John, the notion that Jesus was theos is present (note that the term “son of God” is often assumed to signify that Jesus was divine, but most New Testament scholars would probably not embrace that notion, since the term “son of God” has a wider semantic range). In terms of total usage of the word theos in the New Testament, there are 1250+ occurrences.

The Roman writer Pliny the Younger (floruit late 1st and early 2nd century) penned a description of the Christians, including their meetings, to the Emperor Trajan (r. ca. 98-117 CE). Among the things that he said is that they had “met regularly before dawn on a fixed day to chant verses alternately among themselves in honor of Christ as if to a God….” (Latin: “…Christo quasi deo…”Pliny, Book 10:7). Similarly the Emperor Julian also mentions that Christians of his day embraced this same notion, namely, that Christ was God (as noted above). Julian, of course, argues against this view (so Wilken 1984, 179). In any case, the main point is that the belief that Jesus was God is found, at the very least, in the New Testament gospel of John, and non-Christian Romans also consider this to be something that Early Christians affirmed (i.e., at least some of them, with the exception of Ebionite Christians of the 2nd century, Arius of the 4th century and his supporters, etc.). Thus, it is not entirely surprising that we should find in the Akeptous Inscription words that also presuppose the same thing, namely, that Jesus of Nazareth was Theos, that is, God.

Before moving along to the Women’s Inscription, it is useful to discuss, at least in brief, some of the remaining contents of the Akeptous Inscription.

(1) The name “Jesus,” was a common name in the First Temple Period and Second Temple Period, with scores of people having this as a first name. In fact, even within the New Testament, it is used of multiple people (including Joshua from the book of Joshua, e.g., in Acts 7:45; Jesus son of Eliezer in the genealogy of Jesus of Nazareth, in Luke 3:29; Jesus Barabbas in certain manuscripts of Matthew 27:16; Bar-Jesus in Acts 13:6). Within the New Testament, the personal name “Jesus” is used ca. 900 times of Jesus of Nazareth. This name comes from a Semitic root (yš‘) word meaning “save,” or “rescue.”

(2) The word “Christ” is a title, and it literally means “the anointed one.” The Hebrew equivalent of this term is the word “Messiah” (used in John 1:41; 4:25), which also literally means “the anointed one.” It should be remembered that prophets, priests, and kings (in the Hebrew Bible, etc.) were among those anointed with olive oil, often as a means of setting them apart. The term “Christ” is used ca. 500+ times in the New Testament of Jesus of Nazareth.

(3) Also, the personal name Akeptous is definitively that of a woman, since the article modifying “philotheos” is feminine (and singular), namely, η (ē). It is perhaps useful to mention that the recipient of the books of Luke and Acts had a variant of this word as his personal name (i.e., “Theophilus.” Nota bene: like many interpreters, I consider “Theophilus” in Luke 1:3 and Acts 1:1 to be a personal name, especially because the Lucan text uses the term “Most Excellent” in conjunction with that word). Also, the preliminary publication suggests that the personal name Akeptous “seems to be a feminine form of the Latin name Acceptus” (Tepper, Di Segni, Stiebel 2005, 41).

(4) Also, the verb used to signify that Akeptous offered or donated the table is prosphero, which occurs in the New Testament almost 50 times, and so a fairly common word. Within the New Testament, the Septuagint, and Hellenistic literature more broadly, it is frequently used of bringing gifts, and sacrificial offerings, etc. (e.g., Matthew 2:11; Hebrews 8:3, 4; Hebrews 10:11; Hebrews 11:4; Acts 7:42, etc).

(5) The word translated table, that is, trapeza, occurs 15 times in the New Testament. It was used of the table of showbread in the Temple (e.g., Hebrew 9:2, and in the Septuagint usage of the same), any table upon which a meal is placed, from an ordinary meal (e.g., Matthew 15:27; Mark 7:28; Luke 16:21) to the table which the Lucan gospel connects with the Passover meal (Luke 22:21). It is also the term which occurs in the gospels with reference to Jesus overturning the tables of the moneychangers in the Temple (Matthew 21:12; Mark 11:15; John 2:15). It could even be used to refer to a meal itself, that is, the food (e.g., Acts 6:2, etc.). Significantly, Paul uses the word trapeza to refer to a Eucharist table (1 Corinthians 10:21). As for this Worship Hall, the two raised stones in the center could perhaps (from my perspective) have been the location of the table, the upper portion of which could have been more portable and thus not left in this hall when it was ultimately abandoned.

(6) Since Eucharist (cf. the Latin term: Mass) was such a central component of the Early Church’s worship services (e.g., Acts 2:42; Acts 20:7; 1 Corinthians 11:17-34; 1 Corinthians 10:16-17; cf. also Matthew 26:26-30; Mark 14:22-26; Luke 22:15-20), the reference to such a table in this inscription makes perfect sense, as does the word “remembrance” (on this, see the next section). The Early Christian references to worship services, the celebration of the Eucharist, and Agape Feasts are nicely documented in Everett Ferguson’s peerless volume (Ferguson 1999, 79-132).

(7) As noted in the preliminary publication (Tepper, Di Segni, Stiebel 2005, 37), the word for remembrance, mnēmosunon, only occurs three times in the New Testament (the synoptic parallels in Matthew 26:13 = Mark 14:9, as well as in Acts 10:4; the gospel references are to an unnamed woman’s anointing of Jesus with expensive ointment, and the Acts reference states that the prayers of the Centurion Cornelius rose up to God as a memorial). But it should be emphasized that linguistic cognates (verbs, nouns, etc.) with the noun mnēmosunon are present in the New Testament (both verbs and nouns), and these arguably shed even more light on the situation, especially since some of these are connected with remembering Jesus of Nazareth in connection with the Eucharist (e.g., 1 Corinthians 11:24, 25; Luke 22:19).

B. The Women’s Inscription: Readings, Transliteration, and Translation (with word-division added).

1. ΜΝΗΜΟΝΕΥΣΑΤΕ (mnēmoneusate)

2. ΠΡΙΜΙΛΛΗΣ ΚΑΙ ΚΥΡΙ- (primillēs kai kuri-

3. –ΑΚΗΣ ΚΑΙ ΔΩΡΟΘΕΑΣ (akēs kai dōrotheas)

4. ΕΤΙ ΔΕ ΚΑΙ ΧΡΗΣΤΗΝ (eti de kai chēstēn)

Within the preliminary publication, the following very fine translation is given: “Remember Primilla and Cyriaca and Dorothea, and moreover also Chreste” (Tepper, Di Segni, Stiebel 2005, 41). The preliminary publication also notes that Primilla is a “good Latin name, a diminutive of Prima” (Tepper, Di Segni, Stiebel 2005, 42). As for the remaining three names, the preliminary publication notes that the other three names are “common Greek names.” Finally, it is worth noting that the preliminary publication cautiously entertains the possibility that the women named in this inscription were martyrs, based on references to Christian women martyrs in the early part of the 3rd century CE. (Tepper, Di Segni, Stiebel 2005, 42). This is certainly possible, but I am disinclined to suggest this as something that should be considered probable. There is just not enough evidence to suggest this. Of course, it may very well be that all four of these women who are to be remembered have passed away (i.e., are dead), but the cause of death is not something that one can ascertain in this case.

In terms of the meaning of the names, the following can be said: the name Primilla means essentially “first.” As for the other names, Dorothea is a Greek name meaning “Gift of God.” Chreste is a Greek personal name meaning “useful,” “suitable,” “kind,” “benevolent” (cf. Paul’s pun in Philemon 11). Kuriake (which is the way I prefer to transliterate this name, rather than Cyriaca) essentially is an adjective meaning “belonging to the Lord,” and as an adjective, this word actually occurs in the New Testament as a way of referring to the “Lord’s supper” (1 Cor 11:20) and the “Lord’s Day (Revelation 1:1), with “Lord’s” a means of referring to Jesus of Nazareth. It is at least plausible to suggest that Kuriake is a nickname, as nicknames are nicely attested in the New Testament (e.g., Peter, Barnabas, etc.). On the other hand, one could also envision Christian parents giving this name to a daughter. And, of course, since the term “lord” is not a distinctively Christian term (i.e., it occurs in a wide variety of contexts in Greek literature), nothing certain can be deduced from this personal name.

Here are some additional philological details. The word mnēmoneusate is an aorist, active, imperative, 2nd person plural from the verb mnēmoneuō. This verb occurs 21 times in the New Testament. The usage is broad, hence, within the New Testament it is used of remembering the miracle of the five loaves (Matthew 16:9 = Mark 8:18), remembering the word(s) of Jesus (John 15:20; Acts 20:35), remembering the poor (Galatians 2:10), remembering the resurrection of Jesus Christ (2 Timothy 2:8), remembering Paul’s labor and toil among the churches (1 Thessalonians 2:9). Perhaps most relevant for the Women’s Inscription, people are also to be remembered, thus, there is a command to remember Lot’s wife (Luke 17:32), and Paul mentions that he remembers the Thessalonians and their work in his prayers (1 Thessalonians 1:2-3).

It is particularly interesting that of the seven people named in these inscriptions, five are women, and just two are men (i.e., the centurion and the artisan responsible for laying the mosaics). In this connection, in terms of women within Early Christianity, including within the New Testament period, it is useful to emphasize that Paul mentions a woman named Phoebe (referred to as “our sister”) at the church in Cenchreae, refers to her as a Deacon (Greek: diakonos, the same word used of men I 1 Timothy 3:8) of the church in Cenchreae, he commends her highly, and he encourages the Christians in Rome to welcome her, because she has been a benefactor to many, including him (Romans 16:1). And within this same pericope (paragraph), Paul mentions Prisca (Priscilla) and her husband Aquila, who have been instrumental in his own life (cf. also Acts 18:2, 18, 26; 1 Corinthians 16:19 2 Timothy 4:19). A verse or two later, he encourages the Roman Christians to “greet Mary,” as well as a man named Adronicus and a woman named Junia (Julia), who were imprisoned with him for a time and who are “highly esteemed among the apostles,” and the list goes on with additional women and men mentioned (Romans 16:3-16). Paul also mentions women praying and prophesying (1 Corinthians 11:3-5), and in Galatians, Paul wrote: “There is no longer Jew nor Greek, slave nor free, male nor female…” (Galatians 3:28). In other words, within Pauline writings, women were highly esteemed.

In terms of the broader New Testament (i.e., not just the Pauline material), there are additional references, which shed more light as well. In the book of Acts, there is reference to the Deacon Philip whose four unmarried daughters were prophetesses (Acts 21:9). Furthermore, a certain Lydia from the city of Thyatira, a dealer in purple cloth, and a convert to Christianity, is mentioned prominently (Acts 16:11-15). Along these same lines, Luke mentions a prophetesses named Anna (Luke 2: 36), and he also states that Mary Magdalene, Joanna (the wife of Chuza, Herod’s steward), Susanna, and many other provided support for Jesus and his disciples “out of their means” (Luke 8:1-3; cf. also Luke 24:10; Luke 23:27, etc.). In addition, all four canonical gospels state that there were women (or even, “many women,” in the Matthean account, etc.) were present at the crucifixion, with specific mention of Mary the wife of Clopas, Mary the mother of James and Joseph, the mother of James and John, a certain Salome, and Mary Magdalene, as well as Jesus’ mother, were present at the crucifixion (Matthew 27:55-56; Mark 15:40-41; Luke 23:49; John 19:25-27). And all four canonical gospels also name this same basic group as among those at the tomb and witnesses to the resurrection (Matthew 28:1-8; Mark 16:1-8; Luke 24:1-12; John 20:1-13). In this connection, it should also be noted that, according to the New Testament, some of Jesus’ miracles were performed at the behest of, or for, women (e.g. Matthew 15:21-28 = Mark 7:24-30; Luke 7:11, etc.). And Jesus’ friendship with Mary, Martha, and Lazarus (the latter being the brother of the former two) is also a motif in some of the gospels (e.g., Luke 10:38-41; John 11:1-44, etc.).

Within certain New Testament texts, a lower view of women can be prominent (perhaps most strikingly, 1 Timothy 2:8-15, a book which is often classified as Deutero-Pauline, as well as in the so-called “household codes,” Haus-tafeln of Ephesians 5:22-6:9 and Colossians 3:18-4:1, both of which are books also often classified as Deutero-Pauline or the like).

In sum, the prominence of women in the Women’s Inscription, as well as in the Akeptus Inscription, is something that is not surprising, in light of the similar motif present in substantial strands of the New Testament. For convenient reference to some references to women in Early Christian literature outside the New Testament, as well as additional bibliography, see conveniently Ferguson (Ferguson 1999, 225-237). In addition, it is useful to highlight the fact that Pliny the Younger (Pliny, Book 10:8) mentions that in his attempt to ascertain certain facts about Christianity, he tortured two women who were said to be Christian “ministers” (Latin ministrae, a term which is sometimes considered to be the equivalent of diakonos, e.g., the term used of Phoebe in Romans 16:1). In sum, evidence converges nicely to suggest that women could and did sometimes have substantial prominence in Early Christianity (and this was quite different from many segments of the Roman world, in general).

C. The Gaianus Inscription: Readings, Transliteration, and Translation (with word-division added).

1. ΓΑΙΑΝΟΣ Ο ΚΑΙ ΠΟΡΦΥΡΙΣ ΧΡ ΑΔΕΛΦΟΣ ΗΜΩΝ ΦΙΛΟ-

(Gaianos o kai Porphuri(o)s ChR [ChR = ekatontarchēs] adelphos ēmon philo).

2. -ΤΕΙΜΗΣΑΜΕΝΟΣ ΕΚ ΤΩΝ ΙΔΙΩΝ (-teimēsamenos ek tōn idiōn)

3. ΕΨΗΦΟΛΟΓΗΣΕ ΒΡΟΥΤΙΣ ΗΡΓΑΣΕΤΑΙ (epsēphologēse. Brouti(o)s ērgasetai).

Within the preliminary publication, the following very fine translation is given: “Gaianus, also called Porphyrius, centurion, our brother, has made the pavement at his own expense as an act of liberality. Bruitius has carried out the work” (Tepper, Di Segni, Stiebel 2005, 34). My translation is slightly different: “Gaianos, who is also called Porphyry, a centurion, our brother, having earnestly desired to do so, has commissioned this mosaic-inscription. Brutus has done the work.” Within the preliminary publication, it is noted that the name Porphyrius is Greek. It is also suggested that the name Gaianus “in spite of its Latin sound, may well be a transcription of the Arab name Ghaiyan.” It is also noted that, of course, the name “Brutius,” is a good Latin name (Tepper, Di Segni, Stiebel 2005, 35).

Before delving into a few philological details of this dedicatory inscription (i.e., the Gaianus Inscription), I wish to discuss a particular type of the “double-name phenomenon” (which is distinct from nick names, and the like). Thus, note that the phrase “Gaianos o kai Porphurios.” Gaianus also called Porphyrius” is the very same phrasing as is found in the book of Acts with regard to Paul (in Acts 13:9). That is, Acts uses the following phrase Saulos o kai Paulos (it should be remembered that de is postpositive, so I have not included it here, as I focus on the relevant phrase itself), that is “Saul the one also (called) Paul.” And along these lines, it is useful to emphasize that it has often been stated that Saul changed his name to Paul after his conversion. In spite of his popularity in semi-popular contexts, this is not a particularly accurate construal of the evidence. Note, therefore, that Saul’s conversion is recorded in Acts 9 (he is introduced into the narrative of Acts in Acts 7:58, and he is then the focus of much of Acts 8). Notice, however, that he is referred to as Saul not only in the remainder of Acts 9, but also in Acts 11:25, 30; Acts 12:25; Acts 13:1, 2, 7. Then, in Acts 13:9 he is referred to as “Saul the one who is also (called) Paul.” Thus, first and foremost, I would emphasize that the usage of the name “Paul” does not begin right after the conversion at all. Second, I would emphasize that the biblical text certainly does not say “Saul who is now called Paul.” Third, when the name Paul is introduced in the narrative, Paul has just embarked on his first missionary journey, and he and Barnabas are in the presence of a Gentile named Sergius Paulus (a proconsul). That is, the impetus for the reference to the name Paul is that he is now among Gentiles and so his Gentile name is used. In other words, Paul had two names: his given Hebrew name (Saul) and the vernacular name which he used in Gentile circles (Paul). Since Paul worked so heavily among Gentiles, he ultimately (in the New Testament) and subsequent history is known by his gentile name.

The same basic double-name phenomenon (i.e., a Hebrew given name and a vernacular name for a diaspora Jew) is well attested in the Hebrew Bible, especially during the Exilic and Post-Exilic Period. Thus, in the book of Daniel, Daniel’s Babylonian name is Belteshezzar, and his three friends Hananiah, Mishael, and Azariah also have Babylonian names, that is “vernacular names” (in addition to their Hebrew names), namely, Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego (Daniel 1;7). The narrative frames these as “other names,” assigned by the palace-master, but the point is that these four figures have Hebrew names and vernacular (in this case, Babylonian) names as well. Along the same lines, Hadassah is Esther’s Hebrew name (Esther 2:7), but she is known in non-Jewish circles as Esther. For an earlier reference (at least in terms of the chronological framing), note that Joseph (in Genesis) was given the name Zaphenath-paneah by pharaoh (Gen 41:45), so he too had a Hebrew name and a vernacular name. In other words, based on the evidence from the Bible itself (in Acts itself, where his conversion is detailed nicely), Paul did not change his name when he was converted. Had this been the case, the name Paul would have been used in Acts 11, Acts 12, and the initial verses of Acts 13. Rather, Paul, like many diaspora Jews (i.e., Jews living outside of Israel and Judah), had a Hebrew name and a vernacular name (i.e., a name used in non-Jewish circles). Ultimately, of course, because Paul’s focus was the Gentile world, it is his Gentile name which he is known for, once he embarked on his first missionary journey and throughout the remainder of his life.

In any case, as for additional philological details with regard to the Gaianus Inscription, the abbreviation for centurion is well attested. Compare also a similar combination of the letters Χ and Ρ (i.e., chi and rhō) which comes to be used (in a similarly ligatured fashion) as an abbreviation for “Jesus Christ” (for discussion and bibliography, see Hurtado 2006, 136, 137). Also, notice that for the names Porphurios and Brutios that the omicron is omitted, an abbreviation of sorts, intended to save at least a modicum of space. The word philoteimēsamenos is an aorist middle participle nominative masculine singular of philotimeomai which can be rendered in various ways. I have chosen (based on certain references in Liddell and Scott) to render it “earnestly desire.” The word epsēphologēse is an aorist active indicative third singular verb of psēphologeō, consisting of two basic morphemes, psēphos meaning a “small stone,” “pebble,” and the morpheme logos (cognate with legō,meaning to say, speak, or even reckon). Finally, one last philological note. The name Porphyry means, in essence, “purple,” or “like purple,” fitting for a person of some stature (because of the association of purple with wealth, power, royalty). It is also very nice that we have the name of the artisan responsible for laying this mosaic, Brutus, a name which means something along the lines of weighty, heavy, or the like.

The fact that a Roman centurion commissioned this inscription is certainly important, especially during such an early period in Christianity. Let’s look at some additional details which provide some background for this inscription and its reference to a centurion who was Christian. The term “centurion” (a leader of ca. one hundred Roman soldiers) occurs ca. 21 times in the New Testament. Upon reading this inscription, the New Testament text that comes most readily to mind is Acts 10, with Cornelius the centurion, the first Gentile convert mentioned in the book of Acts (hence a fairly long narrative about how the Apostle Peter came to embrace him as a convert). According to Acts, he was a centurion of the Italian Cohort, and he was residing in Caesarea Maritime. He is stated to be “godly, and fearing God with his whole household,” a clause that is usually suggested to mean that he was a proselyte to Judaism prior to his conversion to Christianity. Also, it should be emphasized that this pericope of Acts mentions that he sent “a godly soldier” to request that Peter come to his home” (Acts 10:7, 8), and ultimately Cornelius and those close to him were baptized (Acts 10:22-48).

In terms of some of the additional references to Roman centurions in the New Testament, a gospel narrative (Matthew 8:5-13; Luke 7:1-10; John 4:46-54) portrays a centurion requesting that Jesus heal his servant. And in the passion narratives of the gospels, there are references to centurion(s), including one who states that he believed Jesus to be innocent of crimes against Rome (Luke 24:47), with the Matthaean and Marcan parallels containing verbiage suggesting that a centurion concluded Jesus was “the son of God” (Matthew 27:54; Mark 15:39). Mark also narrates a request of Pilate to a centurion to ascertain whether or not Jesus was dead (as a result of the crucifixion), and when the centurion confirmed this, he (Pilate) granted permission to Joseph of Arimathea to bury him (Mark 15:42-47). There are also multiple references in Acts to centurions, as part of the narratives about Paul’s travels after his arrest in Jerusalem (Acts 22:25, 26; Acts 23:17, 23; Acts 24:23; Acts 27:1, 6, 11, 31, 48). In other words, quite predictably, centurions are mentioned multiple times in the New Testament, with some framed in a very positive light.

More generally, chiliarchs (rulers of a “thousand” soldiers) are mentioned ca. 22 times in the New Testament, in various contexts, from the Marcan account of the birthday of Herod Antipas (Mark 6:21), the Johannine account of the arrest of Jesus (John 18:12), to those mentioned in Paul’s travels after his arrest (Acts 21:31-37; Acts 22:24-29; Acts 23:10-22; Acts 24:7, 22; Acts 25:23), and even a couple of references are present in the book of Revelation (Revelation 6:15; 19:18). And the term “soldier” (stratiōtēs) occurs ca. 26 times in the New Testament, in a variety of contexts, with those in the gospels mostly connected with the passion narratives in the gospels, and those in the book of Acts mostly connected with Paul after his arrest (Acts 21; Acts 23; Acts 27), but one with reference to the martyrdom of James the son of Zebedee (Acts 12:4), and the arrest of Peter (Acts 12:6, 18). Among the most relevant gospel references vis à vis this Megiddo Mosaic inscription is the Lucan narrative about some soldiers coming to John the Baptist and asking him what they should do, and John replied that they should “rob no one by violence or by false accusation, and be content with your wages” (Luke 3:10-14). Finally, it should be noted that Early Christian writers (e.g., of the 2nd century CE) discussed the subject of Christians in the military, and it seems that there was some discomfort (among Early Christian leaders) with Christians in the military. The content of these discussions reflects the fact that some Christians were in the military, and even Celsus (a critic of Christianity) seems to suggest the same (for a useful collection of quotations, and some discussion and bibliography, see especially Ferguson 1999, 215-224).

The medallion with the two fish is certainly interesting (and there is a brief but useful discussion of this in a side-bar in the preliminary publication, namely, Tepper, Di Segni, Stiebel 2005, 40). Within the New Testament, the standard word for “fish” is ichthus (ΙΧΘΥΣ). It occurs 20 times in the New Testament, and a diminutive of this word is also attested (ichthudion). Of the New Testament references, the feeding of the 5000 men (andres), plus women and children (Matthew 14:13-21; Mark 6:32-44; Luke 9:10b-17; and John 6:1-15), and the feeding of the 4000 men, plus women and children (Matthew 15:32-39; Mark 8:1-10), with fish and bread as focal points, come rapidly to mind as among the most relevant for the fish imagery here in the Megiddo Mosaic. Various other New Testament texts have fish as a prominent motif, including the Matthaean narrative about the fish and the Temple tax (Matthew 17:24-27, and unique to Matthew), the “miraculous” catch of fish (Luke 5:1-11; cf. John 21:1-11), Jesus referring to the disciples as “fishers of people” (Matthew 4:19; Mark 1:17), and according to a Lucan narrative, a post-resurrection appearance to the disciples (Luke 24:42).

Significantly, during the early centuries of Christianity, fish became a frequent Christian symbol. Along these lines, note that the Greek word ΙΧΘΥΣ came to be used as an acronym, signifying aspects of Early Christian beliefs about Jesus (at least among the Proto-Orthodox), namely, the iota (the first letter of the word ichthus) came to signify the name “Jesus” (as iota is the first letter of the name Jesus), the chi came to signify the word “Christ” (since chi is the first letter of the Greek word for Christ), the third letter, that is, the theta, came to signify the word “of God” (since theta is the first letter of the Greek word theou, “of God”), the fourth letter, that is, upsilon, is the first letter of the word for “son” (uios), and the final letter of the word for “fish,” namely, the sigma, came to be understood as signifying the word sōtēr (other variants of this acronym are attested) In sum, the word ΙΧΘΥΣ was not only the word for “fish” in Early Christianity, but it came to be understood as an acronym for conveying the essence of the Proto-Orthodox beliefs about Jesus, namely, “Jesus” was “Christ,” “the son of God,” and “savior.” Understanding the word “fish” as an acronym is attested already in the Sibylline Oracles (8:217ff) in an acrostic poem on the judgment (see translation by John Collins in volume 1 of James Charlesworth’s Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, 423), in Tertullian (early 3rd century), etc. (for discussion and bibliographic references, see the recent article by Rasimus, 2012, 329ff, et passim). As is also widely known, the motif of the fish is found in Early Christian tomb contexts (e.g., the catacombs in Rome), within baptismal, Eucharist, and burial contexts, beginning in the 2nd century in some cases, and continuing for some time. In sum, the presence of a medallion with a fish fits in very nicely with that which is known about the New Testament and Early Christianity.

Conclusion:

In sum, the 3rd Century Christian Worship Hall mosaic inscriptions are particularly interesting, an archaeological and textual window into Early Christianity, some of its adherents, their beliefs and practices, their prominence, and their diversity. These mosaics will factor prominently in any discussion of Earliest Christianity in the Levantine world, and in the Greco-Roman world in general.

Sources Cited

Adams, Matthew J; David, Jonathan, Tepper, Yotam, “Legio: Excavations at the Camp of the Roman Sixth Ferrata Legion in Israel,” in Bible History Daily, May 1, 2014 (https://www.biblicalarchaeology.org/daily/biblical-sites-places/biblical-archaeology-sites/legio/#note02r).

Brown, Raymond E. “Does the New Testament Call Jesus God?” Theological Studies 26 (1965): 545-573.

______. The Gospel according to John (1-12): Introduction, Translation, and Notes. The Anchor Bible. New York: Doubleday, 1966.

Ehrman, Bart D. The Orthodox Corruption of Scripture: The Effect of Early Christological Controversies on the Text of the New Testament. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Ferguson, Everett, Early Christians Speak: Faith and Life in the First Three Centuries. 3rd edition. Abilene: Abilene Christian University Press, 1999.

Hurtado, Larry. The Earliest Christian Artifacts: Manuscripts and Christian Origins. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2006.

Metzger, Bruce M. Manuscripts of the Greek Bible: An Introduction to Greek Palaeography. New York: Oxford University Press, 1981.

Rasimus, Tuomas, “Revisiting the Ichthys: A Suggestion Concerning the Origins of the Christological Fish Symbolism.” Pp. 327-348 in Mystery and Secrecy in the Nag Hammadi Collection and Other Ancient Literature: Ideas and Practices: Studies for Einar Thomassen at Sixty, edited by Christian H. Bull, Liv Ingeborg Lied, and John D. Turner. Leiden: Brill, 2012.

Tepper, Yotam; Di Segni, Leah, with contribution by Guy Stiebel, “A Christian Prayer Hall of the Third Century CE at Kefar ‘Othnay (Legio): Excavations at the Megiddo Prison. Israel Antiquities Authority, 2005.

Recent Comments