Reflections on the Qeiyafa Ostracon

Building on the sterling work of the authors of the editio princeps, I will be presenting papers on this ostracon at the 2010 Annual Meetings of ASOR and SBL. I will also be publishing an article in a refereed journal on it. At this time, I want to provide a basic summary of this ostracon and its significance, especially in light of the grandiose claims (i.e., in blogs) that have been made regarding it. This material is copyrighted. All rights retained. However, it may be cited in print (with attribution) and bloggers may link to it (or cite from it and then provide a link). From the outset, I should like to note that I consider this to be an important inscription and the rapid publication of it is absolutely commendable.

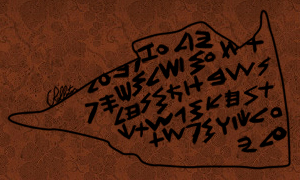

1. This ostracon was discovered on July 8, 2008, at the site of Khirbet Qeiyafa. Expedition Director: Yossi Garfinkel. Site Epigrapher: Haggai Misgav.

2. The writing is ink (not incised). The ostracon is ca. 15 cm x 16.5 cm. The writing is on the concave side of the ostracon. It has been dated in the editio princeps to the 10th century BCE. I am not convinced that it is that late. (Note: “ostracon” is a technical term for a piece of broken pottery with ink writing on it. The plural is “ostraca.” Numerous ostraca have been found in the Middle East. Writing on ostraca is attested on the convex side, the concave side, and on occasion on both sides.)

3. The script of this ostracon is definitively NOT Old Hebrew. For a discussion of the Old Hebrew script, please see my BASOR article. Rather the script of this inscription must be classified as Early Alphabetic (or Proto-Phoenician). The dramatic variations of stance (e.g., the alep) are reflective of this. Furthermore, the fact that such dramatic differences of stance are present is reflective of the fact that we are not dealing with an inscription that comes from a sophisticated scribal guild of some sort. Probably the writer was classed as a “scribe,” but certainly not in the same sophisticated sense that can be said for the writers of the Northwest Semitic inscriptions of the 9th century and later (e.g., Moabite, Old Hebrew, Aramaic).

4. Prior to the rise of the Phoenician script, Northwest Semitic inscriptions could be written sinistrograde (right to left), dextrograde (left to right), or boustrophedon (one line left to right, and the next line right to left). Of course, sometimes NWS inscriptions could even be written vertically. Many people seem to be reading the Qeiyafa ostracon as dextrograde in its entirety. At this juncture, I would note that I am not convinced this is correct, or at least not consistently the case. Because of the difficulties with this ostracon (at the current stage of research…it has just been published), caution should be the modus operandi.

5. It should be noted that typologically, the script of the Qeiyafa Ostracon is definitively older than the 10th century Byblian. For a discussion of the Early Byblian (Phoenician), see my Maarav article. Moreover, it is also older than the Tel Zayit Abecedary.

6. Those stating that the Qeiyafa Ostracon is written in the Hebrew language are probably stating more than the data allow. Among the words that have been mentioned in various places (publications, blogs, etc.) as demonstrative of Hebrew are the following:

A. ‘bd (“do,” “make,” or as a nominal “servant”). However, this root is attested in the Ugaritic language (Late Bronze Age), Phoenician, Old Aramaic, and Egyptian Aramaic (i.e, various Iron Age dialects and languages). Therefore, any suggestion that the presence of the root is demonstrative of Hebrew does not have a secure basis for their arguments.

B. špṭ (i.e., shin, pe, tet). This root, however, is not attested just in Hebrew. Rather, it is, for example, attested in Ugaritic, Phoenician, and in Amorite (see Huffmon), and also in Akkadian. Therefore, it cannot be said that the presence of this word is some sort of an isogloss for Old Hebrew.

C. ‘śh (‘ayin, sin, he, “to do,” “to make”). Again, this word is not one that only occurs in Hebrew. Note, for example, that it also occurs in Ugaritic, Moabite, and even Old South Arabic (demonstrating its presence across much of the landscape of Semitic languages). Note that Benz (1972, 385) suggests that the root may occur in a Phoenician PN, but he also notes that this is not certain. Finally, it should be stated that although this verb(al) [with the negative] is more capable of functioning as an isogloss (for this inscription as written in Old Hebrew), I would suggest that it is not absolutely decisive.

D. The word ’lmnh (“widow”). This root is attested in multiple Northwest Semitic dialects. Most importantly, it has been (by Galil) partially restored. Note that Demsky doesn’t even read this word. Obviously, one should not put great emphasis on a word that is partially restored. Certainly it cannot be the basis for a linguistic classification.

E. mlk (“king,” or “rule”). This word is attested in numerous Northwest Semitic languages, certainly not just Hebrew; therefore, it cannot be used as some sort of isogloss.

The end result of this is that I am not at all certain that the dialect of this inscription can be determined with certitude. Obviously, some have argued that it is definitively Old Hebrew. However, an equally good case can probably be made that it is Phoenician (or at least a reasonable case can be made for that). Ultimately, we can conjecture, but the evidence that is present is fragmentary. Again, caution must be the modus operandi, not definitive statements.

7. It has been argued that this inscription demonstrates that 10th century Israel was a literate state, that the ancient Israelites could have produced literature very early, etc.

A. Obviously, Israel was some sort of a “state” at this point. Our first epigraphic attestation to Israel (as a people group of some sort) is the late 13th century (the Merneptah Stele). Therefore, there is no doubt that there was an Israel as early as the 13th century.

B. Moreover, I have no doubt that literacy was present during the 10th century as part of the fledgling Southern Levantine states (Israel, Moab, Ammon), just as it also was in Phoenicia. However, I am very confident that this literacy was confined to a particular group of elites (i.e., scribes). This is actually a fairly common tenet among scholars of Northwest Semitic (and the Hebrew Bible).

C. Note also that scholars (such as Frank Cross and David N. Freedman) have dated certain portions of the biblical text (namely, poems such as Exod 15 and Judges 5) to periods prior to the 10th century. Although I am not confident that such an early date is at all certain, I would state that I do believe that Old Hebrew was an established (if developing) dialect (language) during and prior to the 10th century BCE. Thus, the discovery of a 10th century BCE Old Hebrew epigraph would not be surprising.

8. Because of its state of preservation, it is difficult to read this ostracon. Moreover, various “renderings” of it have been proposed. Rather than accepting some reading as absolutely decisive (especially one of the sensational ones…which often get much attention, much to my chagrin), it seems to me that it is prudent simply to state that at this time the interpretation of this inscription is at a preliminary stage. As for me, I will release my readings at the ASOR and SBL meetings in Atlanta, with a refereed article coming out at about the same time. Nonetheless, suffice it to say that I am disinclined to see this ostracon as containing some sort of startling content. This is an important ostracon and it joins a relatively rare group of late 2nd millennium and very early 1st millennium linear Northwest Semitic inscriptions, but these recent attempts to sensationalize it should be rebuffed.

Dr. Christopher Rollston (Ph.D. Johns Hopkins University)

Recent Comments