Rollston’s Reflections on the Fragmentary Cuneiform Tablet from the Ophel:

A Critique of the Proposed Historical Context

Introduction

In IEJ 60 (2010): 4-21 a cuneiform tablet (written in Akkadian) from recent excavations in Jerusalem has been published (it will be referred to henceforth as “Jerusalem 1”). It was not found in situ, but rather during the process of “wet sieving,” something that was done “for the contents of loci holding special significance.” The editio princeps was produced in a most timely fashion under the title “A Cuneiform Tablet from the Ophel in Jerusalem.” The authors (Eilat Mazar, Wayne Horowitz, Yuval Goren and Takayoshi Oshima) are to be congratulated for a most expeditious, detailed, and useful publication of this find.

Summary

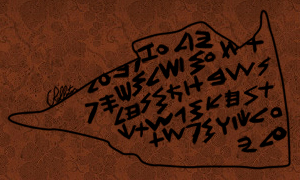

Within the article, the tablet is affirmed to be from the Late Bronze Age (and this seems reasonable, based on the data provided). The soil of the tablet has been analyzed and it was determined that the soil was from the region of Jerusalem. That is, the soil is local and so the tablet was written in Jerusalem (and, thus, not written in some distant region). The obverse and the reverse are inscribed. Very few signs are preserved. According to the editio princeps: the legible words are (as translated into English):

Obverse:

1. [ ]; 2. “You were…[ ]; 3. “a foundation/after for. […]; 4. “to do. […]; 5. [ ].

Reverse:

1. [ ]; 2. [ ]; 3. “they [ ]; 4. [ ];

____

Of course, within the Amarna Corpus, there are several letters from a certain King Abdi-Heba of Jerusalem (Moran, The Amarna Letters, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992; see letter numbers 285-290). This can be, and has been for more than a century, considered a reliable basis for arguing that there were trained scribes in Jerusalem during the Amarna Period (i.e., the reigns of the Egyptian Kings Amenophis III and Amenophis IV). The “Jerusalem 1 tablet” (just published) is of special interest, as it was discovered in Jerusalem and it was also written in Jerusalem; therefore, it constitutes corroborating evidence for a scribal apparatus in Jerusalem during (at least a portion of) the Late Bronze Age, arguably under royal aegis.

The cuneiform script of Jerusalem 1 strikes me as neat and sophisticated (in contrast with some of the Peripheral Akkadian that is known from sites such as Emar, Nuzi, etc.) and within the editio princeps, it is stated that “the hand of Jerusalem 1…can be categorized as higher rather than lower” (i.e., the quality of the script is high). It is also stated that some signs on the Jerusalem fragment “match those of the Abdi-Heba letters (MU, NA, ZI, I, BI, SHU, and A), but some do not (NU, AM, TUM, ISH, AL, and mostly likely SHA, although this sign is not completely preserved on Jerusalem 1.” It is also stated that “the differences between Jerusalem 1 and EA 285-290 do not allow us to identify the scribe of Jerusalem 1 with the scribe (or, more likely, scribes) of the Abdi-Heba letters. In fact, it is our impression that the scribe of Jerusalem 1 shows greater expertise than the scribes of Abdi-Heba in El-Amarna 285-290.” The authors state that in one case (“i-pe-sha,” meaning “to do”) there may be a “clear indication of Amarna-type phraseology,” but they concede that three attested occurrences (which they note) “do not a rule make.”

Strikingly, the authors conclude that “given the fact that the tablet is written on clay from the Jerusalem region and that its find site is close to what must have been the acropolis of Late Bronze Age Jerusalem, there is good reason to believe that the letter fragment does, in fact, come from a letter of a king of Jerusalem, mostly likely an archive copy of a letter from Jerusalem to Pharaoh” (emphasis mine). It is also contemplated that, for Jerusalem 1, the “Jerusalem King in question could be Abdi-Heba,” but the authors also state “but again perhaps not, since Jerusalem 1 does not include any specific feature that would tie it directly to El Amarna 285-290.” They then conclude that “in short, the ductus of our letter fragment would be appropriate for a finely written letter from a king of Jerusalem to the Egyptian court.” It is with the probability of these historical conclusions and Sitz im Leben that I wish respectfully to differ.

Critical Reflections

So, here are the main points that I wish to emphasize, and which I believe serve as a cautionary corrective for the historical context proposed in the editio princeps: (1) There are no personal names that are preserved on this tablet (i.e., on “Jerusalem 1”); (2) There are no titles (e.g., “king”) preserved on this tablet; (3) There are no place names (e.g., “Egypt”) preserved on this tablet; (4) although the script is a fine script, this is not sufficient reason to conclude that this must be “international royal correspondence”; (5) the putative linguistic connections regarding the verb “to do” are arguably simply a reflection of a dialect used in this region during the Late Bronze Age, rather than something that can be said to be distinctively reflective of the Amarna corpus; (6) the chronological horizon of the Late Bronze Age during which this tablet was written cannot be determined on the basis of the archaeological context or the script and so for someone to posit as “probable” a particular historical context is, at best, difficult; (7) Jack Sasson (“Scruples: Extradition in the Mari Archive,” Festschrift fur Hermann Hunger, Wien,2007, footnote 38) has noted that “archive copies,” or “reference copies” are relatively rare (e.g., in the Mari corpus); therefore, the suggestion (in the editio princeps) that Jerusalem 1 is a reference copy is impacted, to some degree, in a negative fashion; (8) finally, it should be noted (as has Erin Kuhns-Darby) that although there is an archaeological context for this tablet, it is certainly not a stratified find…as it was removed from its depositional context and discovered during a “wet sieving” process. All of these things should cause some pause for those positing a precise historical context and Sitz im Leben for this tablet.

I would suggest that “Jerusalem 1” (1) could be some sort of administrative text (2nd person forms are used in memoranda sometimes, as Jack Sasson has noted); (2) could be a legal text, as the 2nd person does occur in legal texts; (3) could be an international letter, of course…but it might be a letter from one official in Jerusalem to another official in Jerusalem, or a letter to a neighboring “city” (e.g., Hazor) or “country” (i.e., Egypt is not the sole country to which a letter might be written); (4) could be a literary text of some sort (as the 2nd person can occur in such texts). Therefore, there are a number of possible options for this tablet. And, thus, because there is such a dearth of actual preserved text on this tablet, I contend that it is best not to attempt to posit as probable this or that historical context, Sitz im Leben, or genre. Ultimately, the fact of the matter is that it could be one of various things…e.g., an epistolary text, a legal text, an administrative text, a literary text. This is certainly not to say that this tablet is not important: it is a significant find. The facets of this tablet that will arguably garner the most interest are those revolving around the Late Bronze Age scribal apparatus of Jerusalem and the aegis thereof.

Christopher Rollston

**Acknowledgments: I am grateful to Adam Bean for proofreading a penultimate version of this article.

____________

ADDENDUM: COMMENTS FROM JOHN HUEHNERGARD

An additional factor is that the reading of line 2 as tab-ša ‘you are’ is problematic. The traces of the signs as copied don’t conform well to the reading. If the tablet was written in Amarna Canaano-Akkadian (which is not certain given the fragmentary state of the text), the reading is also unlikely grammatically: all examples of the verb bašû listed in the Knudtzon glossary are based on the durative ibašši, none on the preterite ibši; further, 1st- and 2nd-person forms of bašû in such Amarna texts are what are called mixed forms: the base is the durative ibašši but the person is marked by suffixes, as in i-ba-ša-ta ‘you are’ in EA 73:40. So I doubt that line two has a form meaning ‘you are’; and that leaves us even less on which to judge what type of text it is.

Sincerely,

John Huehnergard

___________________________________

__________________________________

ADDENDUM: COMMENTS FROM WILFRED VAN SOLDT

There are two lines on the obverse of the new text that I would like to restore as follows:

line 2′, i?-[š]a-am-m[u-ú, “They (will) hear”.

The i- at the beginning is rather dubious, a plene spelling at the end of the word is attested in some Jerusalem letters, cf. EA 285:23 (i-ba-šu-ú) and 286:48 (it-ta-ṣú-ú), but cf. ta-ša-mi-ú in EA 286:50; Moran, Unity and Diversity (1975), 153f.; Cochavi-Rainey, UF 39 (2007), 37ff.

line 3′, iš-tu4 a-na URU […… a/ta/illik(u)], “After I/you/he/they had gone to the city of […]

Recent Comments