Restorations are *not* a Good Foundation for Dramatic Proposals: Reflections on the New, So-called, “Hezekiah” Inscription.

Recently, various press outlets have run stories about a stone artifact with a very fragmentary Old Hebrew Inscription on it (e.g., https://www.israeltoday.co.il/read/bibles-reliability-further-affirmed-as-king-hezekiah-inscription-deciphered/ , citing the proposed restorations and interpretations of Gershon Galil and Eli Shukron), discovered ca. 15+ years ago on an excavation. I would like to make some brief comments on this inscription and the proposed interpretation.

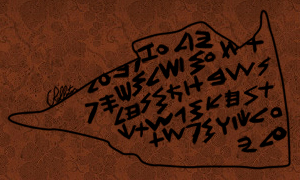

Here are the facts: two fragmentary lines are present. The preserved letters are: (1) […]qyh[…] (2) […]kh.b[…]. The first preserved line may very well contain the end of a personal name, namely, the letter qop, followed by the Yahwistic theophoric element, or a portion thereof. The second preserved line consists of a kap and a hey. After the hey, there is a word divider (indicating that the hey was the last letter of the preceding word) and then a bet (as the first letter of the next word). That’s it. And we don’t know how many lines this inscription consisted of, and we don’t know where in this inscription the two preserved lines fall. And we don’t have the left side or the right side of the inscription.

Although it has been claimed that there are traces of a zayin prior to the qop on the first preserved line, I only see a fractured area of a stone prior to the qop, and if there are traces, they certainly don’t strike me as those of a zayin. In short, the first line just has qyh. The second line just has kh. b .

In terms of the date of the script, the morphology and stance of the letters is consistent with excavated inscriptions hailing from the late 8th or early 7th centuries BCE.

In any case, it has been claimed (as per the link cited above) that the royal name “Hezekiah” can be restored in the first line and that the word “pool” can be restored in the second line, as can also the place-name “Jerusalem” (after the bet). Such a proposal had also been proposed a number of years ago by Peter van der Veen (but without gaining the attention in the press that Galil and Shukron’s proposal has received)

In other words, Galil and Shukron propose to restore two thirds of the root of the name “Hezekiah” (i.e., they restore the het and zayin). And they also propose to restore two thirds of the root word for “pool” (i.e., the bet and resh of the word brkh). And in addition, they propose to restore every single letter of the word for Jerusalem. Mathematically speaking, that’s a high percentage of restoration (i.e., restoring more than twice as many letters as are preserved!). I should add that although the bet in line two is arguably the preposition bet, that’s not the only possible option.

A relevant little anecdote: Long ago, in a doctoral seminar on the Dead Sea Scrolls at Johns Hopkins University, I mentioned some restoration that some scholar had proposed for a lacuna in the scroll which we were reading. Lawrence Schiffman was the professor and I was among the students. I thought that the restoration was reasonable. I will never forget Professor Schiffman’s response: “I don’t spend time discussing restorations” (or something along those lines). At that moment, I recognized the wisdom of Professor Schiffman’s position on restorations, and I adopted it immediately and forever. That is, unless one has very good grounds for a restoration (e.g., boiler-plate phrasing in a legal text, or a text that is repeating something from earlier or later in the document, or something that is citing some other source-document which we also have, etc.), restorations are speculation, and often as foundationless as quick sand.

Naturally, if we had two letters of a tri-literal root, we would be on better footing….but still not necessarily on absolutely secure footing. But we don’t even have two root letters for a single word of this fragmentary inscription! Again, in line one, I see no traces that are demonstrably those of a zayin. Thus, we only have one letter (other than the letter of the theophoric). And the same is true for line two. We don’t have a bet or a resh preserved (or anything else). We only have the final root letter (a kap), and a hey after that. And, as noted, the place-name Jerusalem is entirely absent.

Someone might suggest that restoring a het and a zayin in the first line is good. Well, let’s think about that, and let’s especially think about some other possible personal names, based on personal names attested in the Hebrew Bible and in Old Hebrew inscriptions, personal names which have a qop as the final root letter (as in line one of this inscription). And we could cast our net even further if we wished, that is, personal names in Phoenician and Ugaritic, for example, with qop as the final root letter. But it should be sufficient simply to use Biblical and Epigraphic Old Hebrew (i.e., Old Hebrew inscriptions from the First Temple Period), in order to make the point that there are plenty of other possible personal names that could be restored.

Here are some of them: Bqy, Bqyahu, Bzq (and ‘Adnybzq), Drqwn, Ḥbqwq, Ḥlq, Ḥlqywh, ‘Zqy, Ṣdqyhw, (and ‘Adny-ṣdq, Yhwṣdq, Mlky-ṣdq), Bqbwq, Yṣḥq, ‘zbwq, ‘mwq, ‘šq, Rbqh, Šwbq, Ššq. And this list is certainly not exhaustive. There are more.

And, of course, the same could be said in spades for the proposed restoration of the word for “pool” in line too. Indeed, too much is missing to begin to hazard a guess as to what that word might be. There are scores of possibilities.

Of course, if the question is “could these restorations be correct?,” the answer is yes. But there is a vast difference between suggesting something is “possible” and suggesting it is “probable,” “compelling,” or “certain.” Someone might say, “well, is it plausible?” The answer to that may be yes as well. But there is also a lot of distance between something being “plausible” and something being probable, compelling, or certain.

Well, what’s the best course of action in a case like this? After all, based on ancient evidence, the Siloam Tunnel was something that King Hezekiah commissioned. And it is located in Jerusalem. True enough. But the fact remains that this is a fragmentary stone inscription, it was not found in situ, and in terms of size, the preserved fragment is about the size of the palm of a hand. And since there are many things that it could be, I’d prefer to leave it at that. I wish that this inscription weren’t so fragmentary, but it is. In sum, sensational claims have been made, on the basis of six preserved letters, which are portions of three different words. That is, we don’t even have a single actual word preserved. It’s a bridge too far to draw too many conclusions about this.

Although I do not really like the “could it be” game, it may be useful for me to play this game for just a moment. Thus, if line one does contain a personal name, could it be the name of a stone-mason responsible for the inscription (as some have suggested for the name ‘Oniyahu of Khirbet el-Qom), or could it be the name of some high official (e.g., of the palace, as in the Royal Steward inscription, or of the temple), or could it be some military official of Judah, or could this even be the fragmentary remains of a list of officials (we do have such lists in the book of Kings)? Could it be some sort of a memorial inscription, mentioning some great figure of the past (known to us, or not known to us)? Or again, in terms of date, must this inscription be from the time of the completion of the tunnel (late 8th century), or, since this water tunnel was used for some time after the late 8th century, could it be the name of someone (e.g., from one of the above categories) from the early 7th century (as the script would allow)? Ultimately, the answer to all of the above questions is certainly yes, at least at the theoretical level. And that’s the problem with speculation. We just don’t know. And in addition to all of this, the content of inscriptions, even monumental ones, sometimes surprises us (within the broader field of Northwest Semitic)…making speculations particularly precarious. On top of all this, we do not have a full list in the Hebrew Bible of all the officials of the palace, temple, or military of ancient Judah in the 8th or early 7th centuries. Thus, I prefer not to speculate about such things [nota bene: I added this paragraph on November 10 around 7:00 am eastern, about twelve hours after the original post, as a reply to Danel Kahn’s very useful comment].

One final note is perhaps useful, before I conclude this post. According to the Israel Today article (cited above), Gershon Galil stated that “since until today it was commonly accepted that the kings of Israel and Judah, unlike the kings of the ancient Middle East, did not make themselves royal inscriptions and monuments… to commemorate their achievements.”

It is true that some scholars have suggested this. But quite a few have stated that Israel and Judah did produce monumental inscriptions. Indeed, in my volume entitled “Writing and Literacy in the World of Ancient Israel: Epigraphic Evidence from the Iron Age,” I cite a few inscriptions that, although fragmentary, qualify as monumental inscriptions in Old Hebrew. In other words, some of us have contended (long ago) that Israel and Judah did produce monumental inscriptions and also referred to some that qualify.

Well, such are my brief methodological musings about these recent claims regarding a particularly fragmentary inscription, with the six preserved letters that constitute the partial remains of three different words.

Christopher Rollston, George Washington University (rollston@gwu.edu)

Recent Comments